Gaspee Virtual Archives Virtual Archives |

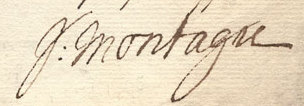

| Admiral

John

Montagu (1719-1795) The Gaspee Days Committee at www.gaspee.COM is a civic-minded nonprofit organization that operates many community events in and around Pawtuxet Village, including the famous Gaspee Days Parade each June. These events are all designed to commemorate the 1772 burning of the hated British revenue schooner, HMS Gaspee, by Rhode Island patriots as America's 'First Blow for Freedom' TM. Our historical research center, the Gaspee Virtual Archives at www.gaspee.ORG , has presented these research notes as an attempt to gather further information on one who has been suspected of being associated with the the burning of the Gaspee. Please e-mail your comments or further questions to webmaster@gaspee.org. |

| Selected excerpts without commentary: |

| From:

Centre for Newfoundland

Studies Archives, Memorial University Library, April

1997 http://www.library.mun.ca/qeii/cns/archives/montagu.php?print=1

Montagu returned to active duty in 1757 as captain of the Monarque, and one of his first responsibilities was to carry out the sentence of the court martial of Admiral John Byng (Governor of Newfoundland 1742) who had been found guilty of negligence for his decision to retreat from the French forces at Minorca the previous year. Byng was shot by firing squad on the quarter-deck of the Monarque on March 14.

While in charge of the Newfoundland station, Montagu was mainly concerned with protecting the coast and the fishing fleet from American privateers. He succeeded in this by outfitting "a number of the best fast sailing vessels in the trade ... as armed cruisers, putting young lieutenants, masters, mates, midshipmen, and petty officers in charge of them. With the men-of-war under his command and these improvised sloops and cutters, he most effectively protected our coasts from the American privateers." (D.W. Prowse: 1895, pp. 340-1) With the outbreak of renewed hostilities with France in 1778, he ordered the capture of St. Pierre and Miquelon, had the town burned, and the 1392 residents sent back to France. His tour of duty in Newfoundland ended in 1778 and he returned to England. From 1783 to 1786 he served as Commander-in-Chief at Portsmouth and rose through the admiralty ranks, being made Admiral of the White Squadron on September 24, 1787. He retired to Fareham in Hampshire, where he died on September 7, 1795. |

|

From:

Berryhill &

Sturgeon Historical Documents <http://berryhillsturgeon.com/> Montagu

commanded the North American Squadron from

August 1771 to July 1774, a

very trying period. He was embroiled in the

Gaspee affair, the Gaspee

Commission, the Boston Tea Party, and, as a

final gesture, it was

Montagu who initiated the naval blockade of

Boston under the terms of

the Boston Port Act. He was the most disliked of

all the men who held

the North American naval command. The Boston Tea

Party was a protest by

the American colonists against Great Britain in

which they destroyed

many crates of tea on ships in Boston Harbor.

The incident, which took

place on Thursday, December 16, 1773, has been

seen as helping to spark

the American Revolution. England reacted

with the Boston Port

Act. The Boston Port Act, passed by the British

Parliament and becoming

law on March 31, 1774, is one of the measures

(variously called the

Intolerable Acts, the Punitive Acts or the

Coercive Acts) that were

designed to secure the United Kingdom's

jurisdictions over her American

dominions. A response to the Boston Tea Party,

it outlawed the use of

the Port of Boston for "landing and discharging,

lading or shipping, of

goods, wares, and merchandise" until such time

as restitution was made

to the King's treasury (for customs duty lost)

and to the East India

Company for damages suffered. In other words, it

closed Boston Port to

all ships, no matter what business the ship had.

Service

history: 1733

trained at Royal Naval Academy at Portsmouth,

1740 promoted lieutenant and served on the Buckingham, 1744 present at the Battle of Toulon, 1757 present at the execution of Admiral John Byng, 1770 promoted to Rear-Admiral of the Blue, 1771 — 1774 commander-in-chief of the North American station, 1776 promoted Vice-Admiral, 1776 commander-in-chief and governor of Newfoundland, 1782 promoted Full Admiral of the Blue, 1783 — 1786 commander-in-chief of Portsmouth 1787 promoted Full Admiral of the White, |

| From: Montague

Millennium http://www.montaguemillennium.com/familyresearch/h_1795_john.htm John Montagu,

1719-1795 Entered Royal Academy, Portsmouth, 1733; served on the Dreadnought, Shoreham, Dragon, and Dauphin; lieutenant, 1740; the Buckingham, 1741; Battle at Toulon (but the Buckingham remained in reserve), 1743; witness at court-martial (1743?), accused of being a mouth-piece for his captain:

To flagship Namur, given command of Hinchinbroke, 1744; command of Ambuscade (40 guns), 1747; in Anson's fleet at Battle of Cape Finisterre, 1747; various commands; as commander of Monarque in charge of the execution of Admiral Byng by firing-squad on the quarter-deck, 1757; and at destruction of De la Clue's squadron off Cartagena, 1758; a number of commands; with Hawke at Bay of Biscay, 1760; Rear-admiral, 1770; commander-in-chief, on the North America station, 1771-1774; (the DNB: "defined as `from the River St. Lawrence to Cape Florida and the Bahama Islands'"); vice-admiral, 1776; commander-in-chief at Newfoundland, primarily fighting American privateers, also seized islands of Saint Pierre and Miquelon, 1776-1779; admiral of the blue, 1782; commander-in-chief, Portsmouth, 1783-1786. Until 1749 wrote his name as Mountagu. |

| From: John Adams diary

19, 16 December

1772 - 18 December 1773 [electronic edition]. Adams

Family Papers: An

Electronic Archive. Boston, Mass. : Massachusetts

Historical Society,

2002. http://www.masshist.org/digitaladams/ Page 4 1772

DECR. 29

[i.e. 28?].

Spent the last Sunday Evening with Dr. Cooper at his House with Justice Quincy and Mr. Wm. Cooper. We were very social and we chatted at large upon Cæsar, Cromwell &c. Yesterday Parson Howard and his Lady, lately Mrs. Mayhew, drank Tea with Mrs. Adams. Heard many Anecdotes from a young Gentleman in my Office of Admirall Montagu's Manners. A Coachman, a Jack Tar before the Mast, would be ashamed -- nay a Porter, a Shew Black or Chimney Sweeper would be ashamed of the coarse, low, vulgar, Dialect of this Admiral Sea Officer, tho an a rear Admiral of the Blue, and tho a Second Son of a genteel if not a noble Family in England. An American Freeholder, living in a log House 20 feet Square, without a Chimney in it, is a well bred Gentleman Man, a polite accomplished Person, a fine Gentleman, in Comparison of this Beast of Prey. Page 5 This is

not

the Language of Prejudice, for I

have

none against him, but of Truth. His brutal,

hoggish Manners are a

Disgrace to the Royal Navy, and to the Kings

Service.

His Lady is very much disliked they say in general. She is very full of her Remarks at the Assembly and Concert. Can this Lady afford the Jewells and Dress she wears? -- Oh that ever my son should come to dance with a Mantua Maker. As to the Admiral his continual Language is cursing and damning and God damning, "my wifes d--d A--se is so broad that she and I can't sit in a Chariot together" -- this is the Nature of the Beast and the common Language of the Man. Admiral Montagu's Conversation by all I can learn of it, is exactly like Otis's when he is both mad and drunk. |

| From: Trevelyan, Sir George

Otto. The

American Revolution, Vol 1, New York:

Longmans, Green,

& Co. 1898, page 132. For ten years past

ever

since George Grenville's influence began to be felt in

the distant

parts of the Empire the claims of the Revenue had been

enforced with

unwonted rigour which in the summer of 1771 assumed an

aggressive and

exasperating character. Sandwich, who had

succeeded Hawke at the

Admiralty, had appointed an officer with his own

surname and, as it is

superfluous to state of his own party, to command the

powerful squadron

now stationed in American waters. Admiral

Montagu who came fresh

from hearing the inner mind of the Bedfords as

expressed in the

confidence of the punch bowl was always ready to make

known his opinion

of New England and its inhabitants in epithets which

on a well ordered

man of war were seldom heard abaft the mast.

The Admiral's appearance was milder than his language. Philip Freneau [the famous poet of the American Revolution] in a satirical Litany prayed to be delivered, From groups at St

James's

who slight our petitions

And fools that are waiting for further submissions From a nation whose manners are rough and abrupt From scoundrels and rascals whom gold can corrupt From pirates sent out by command of the King To murder and plunder but never to swing From hot headed Montagu mighty to swear The little fat man with his pretty white hair It was believed in America that Sandwich and the Admiral were brothers. The story in that shape has got into history. |

| From: Lovejoy, David

S. Rhode Island

Politics and the American

Revolution,

1760- 1776. Brown University Press, Providence, 1969, p160. After attending the

ceremonious

departure of the Boston contingent for Newport, an

English naval

officer described the scene to a friend. It was well

worth the trip

across the Atlantic, he said, just to see "so

respectable a squadron"

as Admiral Montague with his flag and "old mother"

Oliver, the Deputy

Governor, who trembled "under his rusty sword, rigged

out athwartship

like the mizzen yard of a northcountry cat." These,

with Auchmuty, and

his large white wig "(in size equal to Ld.

Mansfield's)" set out

overland for Rhode Island in order to "send to England

for trial and

execution" the people who burned the Gaspee.

Source: Newport Mercury, April 26, 1773. Owing to winter conditions Admiral Montague traveled overland to Swansea on the Taunton River where he boarded a vessel for the remaining part of the trip to Newport. He sailed into the harbor, his Admiral's flag flying, and was promptly saluted by His Majesty's vessels at anchor there. The cannons at Fort George were conspicuously silent, an incident which so infuriated Montague that he refused to call upon Governor Wanton and wrote home to the Lords of the Admiralty bitterly complaining about the insult he had received. Source: Newport Mercury, Jan. 25, 1773 |

| The above story continues

in:

Stout, Neil R. The

Royal Navy in

America, 1760-1775: A Study of Enforcement of British

Colonial Policy

in the Era of the American Revolution. Naval

Institute Press,

Annapolis, MD, 1973, p159: Montagu's complaint

was

laid

before the king, who, according to Lord Dartmouth, the

new Colonial

Secretary, was "justly incensed" and ordered that "his

Majesty's ships

of war, coming into any of the ports within the colony

of Rhode Island,

and having an admiral's flag or broad pennant hoisted,

be saluted in

such manner as is usual in all other parts of his

Majesty's dominions

in America."

p155Montagu commanded

the

North

American Squadron from August 1771 to July 1774, a

very trying period.

He was embroiled in the Gaspee affair, the Gaspee

Commission, the

Boston Tea Party, and, as a final gesture, it was

Montagu who initiated

the naval blockade of Boston under the terms of the

Boston Port Act. He

was the most disliked of all the men who held the

North American naval

command.

P199: COMMANDERS

OF THE NORTH AMERICAN SQUADRON OF THE ROYAL NAVY,

1759-1776

|

| Back to Top | Back to Gaspee Virtual Archives |

John

Montagu was born in

1719 in

Lackham, Wiltshire, the son of

James Montague and a great-great-grandson of the first

Earl of

Manchester. Montagu entered the Royal Academy at

Portsmouth on August

14, 1733 and served on board a number of vessels

during the next seven

years. He was promoted to lieutenant on December 22,

1740 and assigned

to the Buckingham the following February. He

attained the

rank of commander in March 1744/5, and was made

captain in January

1745/6 on board the 40-gun ship Ambuscade,

seeing action at

Cape Finistre the following May. He saw limited

command in the eight

years between 1748 and 1756, during which time he

served as Member of

Parliament for Huntington.

John

Montagu was born in

1719 in

Lackham, Wiltshire, the son of

James Montague and a great-great-grandson of the first

Earl of

Manchester. Montagu entered the Royal Academy at

Portsmouth on August

14, 1733 and served on board a number of vessels

during the next seven

years. He was promoted to lieutenant on December 22,

1740 and assigned

to the Buckingham the following February. He

attained the

rank of commander in March 1744/5, and was made

captain in January

1745/6 on board the 40-gun ship Ambuscade,

seeing action at

Cape Finistre the following May. He saw limited

command in the eight

years between 1748 and 1756, during which time he

served as Member of

Parliament for Huntington. Montagu

saw action in

various

European engagements during the Seven

Years' War (1756-1763). In 1770 he was made Rear

Admiral of the Blue

Squadron and the following year made

Commander-in-Chief of the North

American station, from the Gulf of St. Lawrence south

to Florida and

the Bahamas, a position he held until 1776 when he was

made

Commander-in-Chief and Governor of Newfoundland. In

February of that

year he was raised to Vice Admiral of the Blue.

Montagu

saw action in

various

European engagements during the Seven

Years' War (1756-1763). In 1770 he was made Rear

Admiral of the Blue

Squadron and the following year made

Commander-in-Chief of the North

American station, from the Gulf of St. Lawrence south

to Florida and

the Bahamas, a position he held until 1776 when he was

made

Commander-in-Chief and Governor of Newfoundland. In

February of that

year he was raised to Vice Admiral of the Blue.