|

Introduction

This paper presents a survey of the literature covering the more

significant papers about the Gaspee

uncovered to date and the more general ship construction and rigging

practices of the mid-eighteenth century. I have attempted to synthesize

the available information and draw my own conclusions about what can be

determined today about the actual construction and rigging of the Gaspee as of the time of her

burning in Narragansett Bay.

Background

"In January 1764, the Admiralty began buying schooners for service

mostly along the New England coast…Hence, the Admiralty ordered the

Navy Board to obtain six "Marblehead schooners or sloops" to be named Chaleur, Gaspee, Hope, Magdalen, St. John,

and St. Lawrence…." The

Navy List shows these vessels to have been nearly alike in size: Magdalen 90 3/94; Gaspee, 102 44/94; Hope, 105 40/94; St. John and St. Lawrence 114 65/94 and Chaleur 116 91/94. Chaleur is the only one of these

vessels for which Admiralty draughts are known to exist.

The name "Marblehead" is generally accepted today as indicative of

vessels built only in Essex County, Massachusetts. Chapelle and

others indicate that this definition was also true during the

eighteenth century. The Admiralty papers, as reported by

Chapelle, reference "Essex" as one of two areas on the North American

coast that were recognized as centers for building fast sailing

vessels. Hahn, on the other hand suggests that to the Admiralty

and their purchasing agent Colville, a looser definition was in

operation.

Hahn presents much of a long letter from Admiral Colville, writing from

Halifax Harbor, to Philip Stephens, Secretary of the Admiralty

detailing the progress in acquiring "six Marblehead Schooners or

Sloops". I quote in part "on the 27 Directions were sent to

Boston, by the Naval Officer, for purchasing three of the best

Marblehead Schooners or Sloops, from Seventy to ninety Tones that could

be procured, to be delivered at this Place." In a later letter,

Colville identifies the three as Magdalen,

Schooner, 90 3/94 tons; Chaleur,

Sloop, 116 91/94 tons; and St. John,

Schooner, tonnage unknown.

Further in Colville's letter, he goes on to say "Besides these, two

Schooners were purchased at this Place which are now fitting out, at

the Yard, in the manner directed by their Lordships: They are very fine

Vessels between Ninety and a hundred Tons each; one of them was built

last Fall at a new Settlement of this Province called Chester, twelve

Leagues to the Westward of Halifax… I expect another Schooner that is

ready to be launched at the same Place which will compleat [sic] the number of six. In

the later letter, he identifies these vessels as; Hope, Schooner, 105 40/94 tons; St. Lawrence, Schooner, 114 65/94;

and Gaspey [sic], Sloop, 102 44/94.

From Colville's letter we then have three vessels, not including the Gaspee, which were purchased at

Boston, where they were built unknown. We also have three

vessels, including the Gaspee,

which were purchased at Halifax. One of them is not identified to

her place of building. One of them positively identified as being

"built" at Chester which was probably Hope

since her age was given as 9 months. There is a strong suggestion

that a third vessel is being built at Chester as opposed to just going

through a refit, by the comment "I expect another Schooner that is

ready to be launched at the same Place which will compleat [sic] the number of six". Of

the vessels procured in Halifax, Colville already had two in hand at

the time of writing the letter and was waiting for the third. In his

letter, Colville states “this is the worst time of the year for

buying such Vessels, as most of them are fitted out for the Summer’s

Fishing when that Season is over they become plenty and cheap”.

In his final tabulation of vessels purchased at Halifax, Colville had

two schooners and a sloop, not the three schooners he had originally

reported. The Gaspee

was reported as the "sloop" and her age of 1 year 7 months prohibits

her consideration as being the vessel that was under construction at

the time the first letter was written. Evidently, Colville bought

a different vessel rather than wait for the one that was not yet

launched.

What we are left with is six vessels that were built between 1761 and

1764 somewhere between Halifax and Boston, give or take a few miles

further north or south, that in the eye of Admiral Colville and his

aids fit the description "Marblehead schooner or sloop".

Hull Form

Left: Draught of Chaleur, courtesy of the Joseph Bucklin Society

website at http://www.bucklinsociety.net Left: Draught of Chaleur, courtesy of the Joseph Bucklin Society

website at http://www.bucklinsociety.net

Click image to enlarge.

Reliable

draughts

exist only for the Chaleur out

of the six ships in question. Draughts are also available for two ships

of the same period, the Halifax

and the Sultana. The only extant

dimensions recorded for the Gaspee

are her tonnage (102 44/94), length of keel (49), extreme breadth (19’

10”) and depth of hold (7’ 10”). Smith and Gilmer estimate the length

on the keel to be 46-52 feet, LOA 63-68 and beam 19-21 for a vessel of

100 tons. Although the Gaspee

dimensions compare favorably to the estimates, the estimates represent

a composite of the known hull forms of the period. Knowing exact

dimensions does not give an indication of the hull form without

comparison to other vessels. The following table shows the dimensions

to Gaspee, Chaleur, Halifax and Sultana.

| Ship |

Tonnage |

Keel |

Range of Deck |

Beam |

Hold |

| Gaspee |

102.47 |

49.00 |

68* |

19.83 |

7.83 |

| Chaleur |

116.97 |

50.00 |

70.67 |

20.33 |

7.29 |

| Halifax |

106.50 |

46.88 |

58.25 |

18.25 |

8.83 |

| Sultana |

52.62 |

38.46 |

50.5 |

16.06 |

8.3 |

* Estimate by H. Chapelle, letter

dated 20 December 1966 to David Stackhouse, Gaspee Days Committee

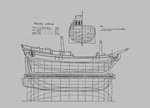

Left: The lines and outboard

profile of the Halifax,

(misspelt as Hallifax on this draught) an

American-built

commercial

schooner c1765. The plan shows a small and rather slow carrier. Note

the

fullness of the waterlines and buttocks at bow and stern. From Chapelle's The

History of American Sailing Ships,

p34-35. Click to enlarge

images.

Right:

Halifax, upper

portion shows the outboard profile

of this schooner as altered for the Royal Navy. The lower portion shows

the inboard details of the schooner before the alterations were made in

her rails. Note the method of fitting the hawse-holes below deck level,

an item of construction rarely seen in the period in which this

schooner

was built. Right:

Halifax, upper

portion shows the outboard profile

of this schooner as altered for the Royal Navy. The lower portion shows

the inboard details of the schooner before the alterations were made in

her rails. Note the method of fitting the hawse-holes below deck level,

an item of construction rarely seen in the period in which this

schooner

was built.

The Gaspee compares favorably to the Chaleur and is not too far off from

the Halifax. Either of these

vessels are candidates for possible Gaspee

hull shapes. Because of the relationship between size and hold

capacity, the Sultana is

unlikely to provide insights into the shape of the Gaspee’s hull. In addition to the Chaleur and Halifax drawings, there are extant

wrecks of vessels similar in size from the same period. The wrecks

exhibit similarities to Chaleur

but also exhibit differences that are significant to the actual shape

of the hulls. In some instances, the evident similarities to Chaleur may be a consequence of

the archaeologists using the Chaleur

draughts to lay out their survey grid as was done with the

Terrence Bay Wreck. Taken together, the available evidence leaves a

wide variety of possible hull shapes for the Gaspee.

Left: Drawing of Chaleur, courtesy of the Joseph Bucklin Society

website at http://www.bucklinsociety.net Left: Drawing of Chaleur, courtesy of the Joseph Bucklin Society

website at http://www.bucklinsociety.net

Click image to enlarge.

Some insights

into

selecting an appropriate hull shape could be gained if it could be

determined the purpose for which the Gaspee

was built. Each purpose (e.g., fishing, merchant, transport, privateer

and so forth) tends to favor particular design characteristics. Prior

to the eighteenth century, hull design was general in nature and ships

were built with no particular purpose implied in their design. During

the eighteenth century, more attention was paid in the design toward a

particular occupation, but even then, many vessels served in more than

one occupation. Coleville’s letter gives the information that most of

the vessels procured were “fitted out for the Summer’s fishing” which

implies that in 1763 vessels were still being fitted out differently

for different occupations during different seasons. Chapelle suggests

that Chaleur was built as

both a merchant and a fishing vessel, a common combination from the

period. Gaspee may have been

similarly employed and the economic conditions of the time favor that

conclusion.

One significant clue both Hahn and Morris offer is that in the colonies

during that period, the terms “sloop” and “schooner” were most likely

references to particular hull forms rather than rigging. Morris quotes

Blanckley (1750) as follows: “Sloops are sailed and masted as Men’s

Fancies lead them, sometimes with one Mast, with two, and with three,

with Bermudoes, Shoulder of Mutton, Square, Lugg, and Smack Sails; they

are in Figure either square or round Stern’d.” Morris further

elaborates the issue by stating “three names [in American usage],

sloop, ketch and schooner, do after about 1700 carry with them a

moderately clear association with particular rigs.” Of the six vessels

purchased by Colville, only the Chaleur

and Gaspee are

identified as sloops however, there is no evidence suggesting the

context (hull form or rig) that Colville used in identifying the vessel

types at the time of their purchase. There is evidence that their rigs

were changed from sloop to schooner rigs at some time after being

brought into the navy so at least the context of rig may be assumed.

An additional clue is given in Morris in his identification of vessels

owed at Newport, Rhode Island in 1764 from the Itineraries of President

Ezra Stiles of Yale College. At that time, there were 50 sloops of

average tonnage 60 and 7 schooners of average tonnage 45. This suggests

that for vessels large enough to be noted, sloops were as a class,

larger than schooners. Morris also presents statistics from

Philadelphia from the 1730 Foreign Documents that show the same

characteristics. Unfortunately, all six of the vessels purchased by

Colville are of approximately the same tonnage.

Considerations:

- Gaspee and Chaleur were built within eight

months of each other. This is too short a period for substantial

changes in ship building technology to have come into play.

- Some

variation in

hulls built from the same design can be expected, particularly if they

were built in different yards, but significant variation from type are

unlikely.

- There is no

direct evidence that Gaspee and

Chaleur were of the

same

design.

- Gaspee and Chaleur were approximately the

same size, proportions and tonnage. Size and proportions do not exclude

the possibility of extreme differences in hull form, particularly below

the water line, but nearly equivalent tonnage limits the variation

significantly.

- Gaspee and Chaleur were both identified as

sloops while the other four were identified as schooners.

- Gaspee and Chaleur are known to have been

sloop rigged at the time of purchase.

- Colville,

in

identifying the types of vessels he purchased, may have been referring

to the hull form, the rig or both.

Conclusion: Only

the barest of threads, the definition of sloop used by Colville in

identifying the types of vessels he purchased, connects the design of

the Gaspee to the design of Chaleur. Colville’s definition in

this context is unknown. Without further evidence, the hull form of the

Gaspee cannot be

determined

definitively.

Above the Waterline

Two aspects of a vessel define what she looks like to the casual

observer, her rig and what she looks like above the load waterline. The

characteristics of her look above the waterline include her poop deck,

quarterdeck, bulwarks, rails and the type and placement of the deck

furniture and armament. The unfortunate reality is that for vessels of

this period of the size of the Gaspee,

there is a wide range of possible variation in these characteristics.

Left:

Early woodcut of the attack on the Gaspee, artist unknown. Click image to

enlarge Left:

Early woodcut of the attack on the Gaspee, artist unknown. Click image to

enlarge

Poop Deck:

The oldest extant artistic representations of the Gaspee depict a somewhat oval

transom that exaggerates the curve of the tumblehome. Vessels from the

same period that have a poop deck typically have a change in shape in

the transom that becomes more vertical from the stern view as it

transitions over the end of the poop deck. This transition does not

appear in the oldest artistic representations of the Gaspee and suggests that she did

not have a poop deck. Note that the term “poop deck” was often confused

with the term “quarterdeck” during the period. In this discussion, I

use the term “poop deck” to mean an additional deck in the stern, above

the quarterdeck.

Considerations:

- Contemporary

artists were the “photographers” of their day.

- Contemporary

artists could no more misrepresent a ship than they could a house or a

horse and still stay in business.

- Contemporary

artistic representations of ships may be lacking in small detail, but

in major features may be relied upon.

- None of the

oldest extant artistic representations of Gaspee have been proven to be

contemporaneous.

- Non-contemporaneous

artistic representations tend to be less accurate, the more so as they

become further removed in time.

- Non-contemporaneous

artistic representations may have been intended to emphasize some

aspect of an event other than the vessel involved and to do so in a

manner that increases the perception of degree of difficulty of the

event or the relative importance of the participants.

- The oldest

known

artistic representations agree on major features of Gaspee to a significant degree

although it is possible that they are all reproductions in various

forms of a single, undated woodcut.

Conclusion: The

oldest known

artistic representations suggest that Gaspee did not have had a poop

deck.

Quarterdeck:

Quarterdeck height ranged from mid-shin height to waist height on

vessels of the size of the Gaspee.

In length, they varied from mid-way between the stern and the mainmast

to just forward of the mast. Extant artistic representations give some

indication of the height of the Gaspee’s

quarterdeck. An old woodcut (provenance and exact age unknown but older

than 1856) shows the rounded top to the transom as shown on the plans

of the Chaleur which is known

from the Admiralty draughts to have a high quarterdeck. The people

depicted standing on the quarterdeck are shown well above the waterline

also indicating a high quarterdeck.

Left: Destruction of the

Schooner

Gaspé by J. McKevin,

Engraved by

J Rogers Left: Destruction of the

Schooner

Gaspé by J. McKevin,

Engraved by

J Rogers

engraving

based on earlier woodcarving Found in History of New York, c1872. Click image to enlarge

Hale

reproduces a

steel engraving by J. Rogers which was published in 1856. The

engraving was identified as "after a painting by J. McNevin, from the

Rhode Island Historical Society. The engraving shows the stern

view with marked tumblehome, three widely spaced stern lights and men

standing on the cabin top. The line of the cabin top appears

slightly rounded.

Considerations:

- The length

was

most likely less than the distance between the stern and the mainmast

since she was brought into the British Navy as a warship. A longer

quarterdeck would have interfered with the placement of carriage guns

and would be an unlikely choice.

- A high

quarterdeck is more suitable to providing adequate headroom in the

officer’s quarters.

Conclusion: The

Gaspee probably had a

high

quarterdeck that extended somewhere between one-half and three quarters

of the way between the stern and midship.

Bulwarks:

Most merchant vessels of the period had no true bulwarks in the waist

but rather had bulwarks less than a foot in height. The quarterdeck and

sometimes the forward end of the vessel were edged with a railing.

Fishing vessels, since men fished over the side, typically had a

bulwark in the waist. Small warships sometimes had half-height bulwarks

with notches for the guns similar to the crenellations on a medieval

castle. Others had bulwarks high enough to support the installation of

true gun ports.

Considerations:

- Bulwarks

provide

purchase points for gun tackles.

- Bulwarks

provide

a psychological benefit to the gun crews.

- The Chaleur is shown with full height

bulwarks in the Admiralty draughts.

Conclusion: The

Gaspee probably had

bulwarks

of significant height in the waist after being refitted for use by the

Royal Navy.

Deck Furniture:

Deck furniture provides support for various activities on the deck such

as piloting the vessel, hoisting cargo, sails and anchors and access to

the below deck areas. For any given function, the form and location of

the item could vary, but with some limitations. The companionway for

the aft cabin was unlikely to be mounted in the bow or the mechanism

for hoisting the anchor located in the stern. For a vessel the size of

the Gaspee, there were some

choices that were likely to be preferable to others as indicated below.

Considerations:

- The rudder

was

probably controlled by a tiller, well aft, rather than a wheel. Wheels

of the time tended to have significant play and took up more room than

a tiller alone. Unless a vessel required significantly more mechanical

advantage than offered by a tiller of reasonable length to hold a point

of sail, a wheel was impractical.

- There

was

probably a windlass, rather than a capstain, mounted well forward. It

was probably mounted just abaft the foremast. A capstan was probably

not used due to its requirement for more space to operate than is

needed for a windlass.

- A large

main

hatch was probably just forward of the mainmast. A means of accessing

the hold were required regardless the occupation of the vessel. A

centrally located hatch would give equal access to all parts of the

hold.

- A

companionway to

the cabin was probably installed just aft of the forward edge of the

poop deck. The captain of a vessel needed to be provided with ready

access to the deck from the cabin, particularly in times of imminent

danger to the vessel. That access isn’t likely to have been positioned

such that it encroached on the available cabin space.

- A binnacle

was

probably just abaft the cabin companionway and forward of the forward

end of the tiller. The compass needed to be readily visible to the man

at the helm.

- There may

have

been a cable locker hatch on one or both sides of the bowsprit. Except

in very small vessels, cables were stored below deck. At least one

cable locker is needed. Two is more likely since a vessel of 100 tons

most likely carried a backup anchor.

- There were

likely

to have been one or two elm tree pumps mounted just forward of or on

the quarterdeck. Ships leak. Some means of removing water from the

bilge was needed. Most vessels of the period had a bilge that was lower

in the stern than in the bow. Simple elm tree pumps are most likely for

vessels of the size of the Gaspee.

Conclusion: The

generalities

unfortunately, do not give much insight into the details.

- The

companionway

into the cabin may have been no more than a sliding hatch mounted on

the forward end of the quarterdeck. It may have been a deckhouse

mounted somewhere between the tiller and the forward end of the

quarterdeck.

- The

binnacle may

have been a separate structure or may have been attached to the aft

side of a deckhouse depending on the configuration of the companionway.

- The

literature

indicates that exact placement, shape and size of the deck furniture

was somewhat subject to the whims of the builder during construction or

refit and afterwards, to the whims of the captain.

- There is no

reason to suspect that the deck furniture differed in kind from the

generalities, but there is too much variation possible in actual form

to determine what it looked like on the Gaspee.

Armament:

Bacon reports the Gaspee as a

"schooner of eight guns" but gives no attribution or indication of

their size. Colville’s letter of 19 May 1764 states that he had

commanded the frigate captains to turn over their 3-pounders and part

of their swivels for use on the schooners. Hahn further elaborates that

the difficulty the schooners had in dealing with the smugglers was at

least in part due to their light (3-pounder) armament.

Dudingston claimed at his court martial that he could not train his

guns on the attackers because they were too close to the Gaspee when noticed. This suggests

that the Gaspee was not

equipped with swivel guns since they can be depressed to fire almost

vertically. However, Colville’s letter of 19 May 1764 included swivel

guns.

Considerations:

- Colville’s

letter

gives explicit reference to the size of carriage guns for the Gaspee.

- Eight guns,

mounted in the waist is reasonable for a vessel the size of the Gaspee.

- Guns were

hard to

come by on station. Eight guns may have been desirable, but there might

not have been enough available to meet that goal.

- Swivel guns

were

usually part of the armament of British naval vessels of all sizes

- Duddingston’s

claim of an inability to train guns on the attackers should not be

interpreted to indicate the lack of swivel guns but rather as an

attempt by Dudingston to provide a possible explanation for an apparent

lack of readiness on the part of his officers and crew.

Conclusion:

- Six to

eight

3-pounder guns is a reasonable estimate for the carriage gun armament

of the Gaspee. The carriage

guns were most likely mounted in the waist.

- She was

most

likely also armed with swivel guns mounted on the rail of the

quarterdeck and possibly at the bow.

Rigging:

On the issue of whether "schooner", in reference to rig, meant the same

then as it does now, Morris suggests that at least for Colonial

America, it did, at least in its reference to the number of masts

involved. He claims that the distinction of schooners having two

masts and sloops having one was well part of the local lexicon by mid

century. The oldest extant artistic representations of the Gaspee as of the time of her

burning show her as schooner rigged.

Left: The

Burning of the Gaspee by Charles

DeWolfe Brownell, c1892. Painting courtesy of the Rhode Island

Historical Society. Click image to enlarge Left: The

Burning of the Gaspee by Charles

DeWolfe Brownell, c1892. Painting courtesy of the Rhode Island

Historical Society. Click image to enlarge

The oldest

artistic

representations of the Gaspee

show her as carrying a fore-and-aft sail on both the main and fore

masts and a jib. A square sail mounted on a spar crossed on the

foremast is also shown. There is no spar shown on the main mast. None

of the older artistic representations show a spar crossed on the

mainmast. Both the old woodcut and the later picture by Charles DeWolfe

Brownell (1892) show true topmasts for both the fore and main masts

rather than pole masts. The topmasts appear to have been intended to

support staysails rather than topsails since no yards are shown. This

may however be no more than the particular rig chosen by Dudingston

while cruising Narragansett Bay. Topsail yards were often struck when a

topsail was not needed to meet the sailing conditions at a particular

point in time. Staysails, in light airs, are more useful in the general

sailing conditions of Narragansett Bay than topsails.

May reports testimony to the effect that "One of the boats came

alongside under the starboard fore shrouds". The existence of

shrouds, both fore and aft, are to be expected in a vessel of this type

and period.

The Gaspee was purchased into

the British navy as a sloop that was later converted to a schooner.

This is a reasonable conversion for the period, particularly when there

was inadequate crew for the vessel. Sloops require a larger crew than

do schooners of the same size due to a sloop having a single, very

large mainsail in comparison to the schooner’s smaller fore and main

sails. Coleville indicated in his letter to the Admiralty that he was

having difficulty obtaining an adequate number of skilled seamen to man

the fleet.

The references to the Gaspee

being a schooner describe a vessel whose rig falls within the

parameters established by the oldest known artistic representations.

Considerations:

- All

references to

the Gaspee, at the time of

her burning refer to her as a schooner.

- The term

schooner, as applied to rig, was at the time equivalent to the usage of

the term today.

- The basic

schooner rig supports a fairly broad set of optional sail plan

configurations depending on the prevailing weather conditions.

- All

reasonable

artistic representations of the Gaspee

depict a schooner rig.

Conclusions:

- The oldest

artistic representations are probably a reasonable estimate of the

rigging configuration of the Gaspee

at the time of her burning.

- The

configuration, at the time of her burning, does not preclude other

configurations she might have carried at other times, that still remain

within the definition of schooner as applied during the period.

Summary of Conclusions

Some reasonable assumptions may be drawn from the available

documentation about the Gaspee’s

construction and rigging. These are however limited to her rig,

armament and generalities about all other aspects of the vessel. The

exact hull form of the Gaspee

has been lost to history, as have most of the details of her

appearance. There are too many gaps in what is known to be able to

definitively describe the Gaspee

to the degree necessary to build a truly representative model or

reconstruction. |

References:

Bacon, Edgar

Mayhew, Narragansett Bay, It's

Historic

and

Romantic Associations, 1904

Biddle, Randle

M,

Personal correspondence with the author.

Chapelle, Howard J. The Search for

Speed Under Sail, W. W. Norton & Co, 1967 Library of

Congress Catalog Card No. 67-11090

Chapelle, Howard J. The History of

American Sailing Ships, W. W. Norton & Co, 1935

Christopher Champlin Papers, Rhode Island Historical Society,

Manuscripts Divison

Hahn, Harold M., The Colonial

Schooner 1763-1765, Conway Maritime Press, 1981

Hale, Stuart O, Narragansett Bay, A Friend's Perspective,

Maritime Advisory Service, NOAA/Sea Grant, Marine Bulletin 42

Harland,

John.,

Personal correspondence with the author

Kenchington, T. J., "An 18th century precursor of the fishing

schooner's 'great beam' or 'break beam'?, The Journal of Nautical Archaeology,

1994 23.1

Kenchington,

T. J.,

Personal correspondence with the author

May, W. E., "The Gaspee Affair", The

Mariner's Mirror, Vol 63 No 2, May 1977

Morris, E. P., The Fore-and-Aft Rig

in America, Yale University Press, 1927

Smith, Melbourne and Gilmer, Thomas C, “The Colonial Brig Peggy

Stewart”, Nautical Research Journal,

Volume 19, No. 4.

Significant Paintings and

Drawings:

Note: Only the oldest provenance sources are considered. More modern

renditions deemed by the author to be too fanciful for colonial built

vessels, even after refit for the British Navy, have not been

considered. Also dropped from consideration are those that lack

sufficient detail to be of use.

|

Virtual Archives

Virtual Archives Right:

Halifax, upper

portion shows the outboard profile

of this schooner as altered for the Royal Navy. The lower portion shows

the inboard details of the schooner before the alterations were made in

her rails. Note the method of fitting the hawse-holes below deck level,

an item of construction rarely seen in the period in which this

schooner

was built.

Right:

Halifax, upper

portion shows the outboard profile

of this schooner as altered for the Royal Navy. The lower portion shows

the inboard details of the schooner before the alterations were made in

her rails. Note the method of fitting the hawse-holes below deck level,

an item of construction rarely seen in the period in which this

schooner

was built.