Gaspee Virtual Archives Virtual Archives |

| Governor (and Chief Justice) Stephen Hopkins (1707-1785) The Gaspee Days Committee at www.gaspee.COM is a civic-minded nonprofit organization that operates many community events in and around Pawtuxet Village, including the famous Gaspee Days Parade each June. These events are all designed to commemorate the burning of the hated British revenue schooner, HMS Gaspee, by Rhode Island patriots in 1772 as America's 'First Blow for Freedom'®. Our historical research center, the Gaspee Virtual Archives at www.gaspee.ORG , has presented these research notes as an attempt to gather further information on one who has been suspected in, or being associated with, the burning of the Gaspee. Please e-mail your comments or further questions to webmaster@gaspee.org. |

| Evidence

to indict Stephen Hopkins: Chief Justice of the Rhode Island Superior Court Stephen Hopkins greatly contributed to the destruction by others of the HMS Gaspee by advising Deputy Governor Darius Sessions in March of 1772 that the actions of the commander of the vessel were probably illegal. In Staples, The Documentary History of the Destruction of the Gaspee, p3: ...I

have

consulted with the Chief Justice thereon, who is of opinion, that no

commander

of any vessel has any right to use any authority in the Body of the

Colony

without previously applying to the Governor and showing his warrant for

so doing and also being sworn to a due exercise of his office—and this

he informs me has been the common custom in this Colony.

Stephen Hopkins was alarmed about the British reaction

to the burning of the Gaspee,

and he and other leading men of the Colony sought advice from the

Revolutionary leader, Samuel Adams. Found in The

Writings of Samuel Adams, Vol II and Vol III, edited by H. A.

Cushing c1904 - 1908.To

Samuel Adams:

Providence

Dec 25, 1772

We doubt not you have before this heard of the difficulties this Colony labors under, on account of the destruction of the Gaspee, they being such as becomes the attention of the Colonies in general (though immediately to be executed on this only). As they affect in the tenderest point the liberties, lives, and properties of all America, we are induced to address you upon the occasion, whom we consider as a principal in the assertion and defence of those rightful and natural blessings; and in order to give you the most authentic intelligence into these matters, we shall recite the most material paragraphs of a letter from the Earl of Dartmouth to the Governor of this Province, dated Whitehall, Sept. 4th, 1772. [Then follows the extract from the Secretary's letter.] You will consider how natural it is for those who are oppressed, and in the greatest danger of being totally crushed, to look around every way for assistance and advice. This has occasioned the present troubles we give you. We therefore ask that you would seriously consider of this whole matter, and consult such of your friends and acquaintance as you may think fit upon it, and give us your opinion in what manner this Colony had best behave in this critical situation, and how the shock that is coming upon us may be best evaded or sustained. We beg you, answer as soon as may be, especially before the 11th of January, the time of the sitting of the General Assembly. Darius

Sessions

Stephen Hopkins John Cole Moses Brown Richard Deasy, writing in his introduction to the 1990 re-publication of Staples, The Documentary History of the Destruction of the Gaspee (p. xxviii) feels that witnesses Hitchcock

and Cole apparently

collaborated

on their testimony concerning events in Sabin Tavern the night of the

raid.

One day before, Brown, Cole, and Hitchcock had told Hopkins that they

intended

to refuse to appear before the commissioners, presumably on the advice

they had received earlier from Sam Adams. Adams had challenged

the

jurisdiction of the commissioners, but Hopkins obviously convinced them

to move away from this kind of direct challenge and to submit written

depositions

instead. Misrepresentation, intimidation, and evasion are all

evident

here in this first session.

Sessions, Hopkins, et al also determined to influence how the Gaspee commissioners were to interpret their special powers. Staples, p49 Thursday,

January 7,

1773.

Stephen

Hopkins, Esq., Chief

Justice of said Colony, also appeared

before

the commissioners and assured them he was ready and willing to aid and

assist the commissioners in the exercise of the power and authority

with

which they are invested for discovering the persons who destroyed the

Gaspee

schooner, &c. The commissioners then requested Mr. Hopkins to give

them in writing a full and particular account of all the proceedings

had

and done by him for discovering and bringing to justice the persons who

committed the aforesaid offence, and also what knowledge or information

he had obtained of the assembling, arming, and leading on the persons

who

perpetrated the same, which he also promised to do without loss of

time.

Of course, Hopkins never did comply with this request, at least not that we have documented. Natalie Robinson states in Revolutionary Fire: The Gaspee Incident that: As a result of this review, and of interviews with Governor

Wanton, Lieutenant Governor Sessions, and Chief Justice Hopkins, the

Commissioners agreed to interpret their powers quite narrowly. They

assured the Rhode Island officials that they would not themselves

arrest anyone or deliver anyone to Admiral Montagu, but would leave

that task to the regular judicial officials in the colony. ... By

acknowledging local judicial authority, the Commissioners calmed some

of the Rhode Islanders' worst fears.

Adding

insult

to injury, Chief Justice Stephen Hopkins issued a warrant for the

arrest of Lieutenant Dudingston in October of 1773 based on the lawsuit

that Jacob Greene & Co. filed against the commander of the Gaspee

for the seizure of their sloop Fortune

the previous March. Hopkins demonstrated a reluctance to find suspects indictable for trial, which would have greatly aided the British cause. In pursuance of Article 3 of their instructions, the commissioners turned over evidence that they had collected to the deputy governor and to the Rhode Island Superior Court (Staples, p95): The honorable the commissioners, appointed by royal

commission, for examining into the attacking and destroying his

Majesty's armed schooner the Gaspee, commanded by Lieutenant

Dudingston, and wounding the said Lieutenant, having laid before us,

Justices of the Superior Court of Judicature, Court of Assize, &c.,

within and throughout the Colony of Rhode Island, two examinations of

Aaron Briggs, two examinations of Patrick Earle, the examination of

Peter May, the examination of William Dickinson, the deposition of

Samuel Tompkins, Samuel Thurston, and of Somerset and Jack, indented

servants, for our advisement thereon:

It appeareth unto us from our consideration had thereupon,

that no particular person or persons are made mention of as being

concerned in that atrocious crime, except in the examination of Aaron

Briggs, a negro, and of Peter May, one of the Gaspee's people. The

confession of the said Aaron upon his first examination was made in

consequence of illegal threats from Capt. Linzee of hanging him (the

said Aaron) at the yard arm if he would not discover who the persons

were that destroyed the Gaspee; and besides, most of the circumstances

and facts related in both of his examinations are contradictions

repugnant to each other, and many of them impossible in their nature. It is evident from the depositions of Tompkins, Thurston, and Aaron's two fellow servants, that he was at home the whole of that night on which the Gaspee was attacked; especially as there was no boat on that part of the island in which he could possibly pass the bay in the manner by him described. In short, another circumstance which renders the said Aaron's testimony extremely suspicious, is Capt. Linzee's absolutely refusing to deliver him up to be examined by one of the Justices of the said Superior Court when legally demanded. Peter May, in his deposition, mentions one person only, by the name of Greene, whom he says, he saw before on board the Gaspee; but the family of Greene being very numerous in this colony, and the said Peter not giving the Christian name or describing him in such a manner as he could be found out, it is impossible for us to know at present the person referred to. Upon the whole, we are all of opinion that the several matters and things contained in said depositions do not induce a probable suspicion, that persons mentioned therein, or either or any of them, are guilty of the crime aforesaid. It is, however, the fixed determination of the Superior Court to exert every legal effort in detecting and bringing to condign punishment the persons concerned in destroying the schooner Gaspee. And if the honorable commissioners are of a different sentiment we should be glad to receive their opinion for our better information. S. HOPKINS, Chief Justice.

J. HELME, M. BOWLER, J. C. BENNET, Assistant Justices |

|

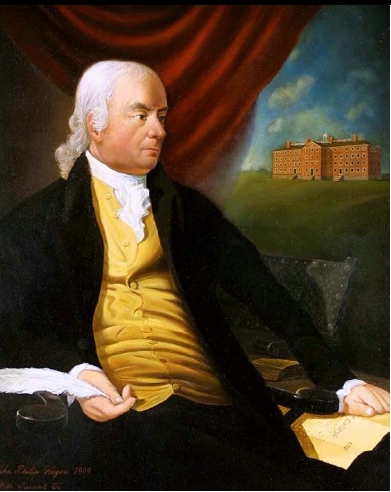

Stephen Hopkins (1707–1785) was an American

political leader from Rhode Island who signed the Declaration of

Independence. He

served as the Chief Justice and Governor of colonial Rhode Island and

was a Delegate to both the Colonial Congress in Albany in 1754 and to

the Continental Congress from 1774 to 1776. He was described by

Rev. Ezra Stiles, subsequently the President of Yale University, as "a

man of penetrating astuitious Genius, full of Subtlety, deep Cunning,

intriguing and enterprising." Stephen Hopkins was born on March 7, 1707 in

Cranston, Rhode Island, the son of William and Ruth (Wilkinson)

Hopkins. He was descended from the Thomas Hopkins that emigrated to

Plymouth Plantation in 1635, and he was raised in his mother's Quaker

religion. His great-granduncle was

Benedict Arnold, the first governor of

Rhode Island (not to be confused with the much later Benedict Arnold

the traitor). He grew up in the small

agricultural community of Scituate to the West of Providence, RI. He

was reared to be a farmer, and had inherited his father's estate in

Scituate, although he was chiefly employed as a land surveyor. He was

later

instrumental in establishing Rhode Island's present-day

boundaries. Hopkins attained success purely by his own

efforts.

He had little formal education, was taught by his fiesty mother and

in the public schools, and he was an avid reader of

Greek, Roman and British history. In 1726 he

married at the age of nineteen to a fellow quaker, Sarah Scott

(c1707-1753), and

fathered

seven children; five sons and two daughters. At least one of his

daughters and one son died in their childhood. After his first wife

died, Stephen Hopkins remarried in 1755 to Ann Smith (1717-1782), her

second marriage also.

His second son, Captain John Hopkins (1728 - 1753) died in Spain of the

smallpox, and Sylvanus Hopkins (1734-1753 was killed by Indians at Nova

Scotia. His youngest son, Capt. George Hopkins (1739 - 1775) is

noted to have also died at sea. When Scituate Township separated

from Providence in 1731, he plunged into politics. During the next

decade, he

held the following elective or appointive offices: moderator of the

first town meeting of Scituate, town clerk, president of the town

council, town solicitor, justice

of the peace, justice and clerk of the Providence County Court of

Common Pleas (in 1733, he became Chief Justice of that court),

Representative

from Scituate to the General Assembly of Rhode Island (1732-1752), and

Speaker of the House (1738-1744 and 1749). He travelled a

considerable distance as the General Assembly met in Newport, some 30

miles South of Scituate and Providence.

Along with his equally famous brother Esek, he bought a store in Providence that led to a successful and profitable career in a mercatile and ship-building partnership. Per Chapin, Howard M., Rhode Island Privateers in King George's war : 1739-1748 (Providence: Rhode Island Historical Society :, 1926, 246 pgs), p177., we find Stephen Hopkins' name in a partnership with that of John Mawney (1718) as owners of the Rhode Island privateerining ship Reprisal, in 1745 during King George's War. For three decades, he built up his business and would probably have acquired a fortune had he not at the same time supported a variety of civic enterprises and broadened his political activities. In 1765 he copartnered with the famous Brown Brothers (Nicholas, Joseph, John and Moses) in establishing the Hope Furnace that created essential cannon for use during the Revolutionary War. His eldest son Rufus Hopkins (1727-1813) was employed in managing the Hope Furnace for almost 40 years.  Right: Detail

inset from Sea Captains Carousing in Surinam (c1752-1758) by John

Greenwood

(1727-1792) courtesy St. Louis Art Museum. Left

to right at table: Nicholas Cooke,

Esek Hopkins, Stephen Hopkins (asleep), and

Joseph Wanton. Click to view entire image. There is some

controversy as to whether this man in red was actually Stephen Hopkins,

as per the said tradition of the original owners of the painting, the

Jenckes family. Brown University professor Robert Kenney believed that

this man must have been Esek and Stephen's other brother, William,

since Stephen was at the time running for

re-election as Governor, and tied up in court in

Worcester MA while suing his arch rival Samuel Ward for slander. Right: Detail

inset from Sea Captains Carousing in Surinam (c1752-1758) by John

Greenwood

(1727-1792) courtesy St. Louis Art Museum. Left

to right at table: Nicholas Cooke,

Esek Hopkins, Stephen Hopkins (asleep), and

Joseph Wanton. Click to view entire image. There is some

controversy as to whether this man in red was actually Stephen Hopkins,

as per the said tradition of the original owners of the painting, the

Jenckes family. Brown University professor Robert Kenney believed that

this man must have been Esek and Stephen's other brother, William,

since Stephen was at the time running for

re-election as Governor, and tied up in court in

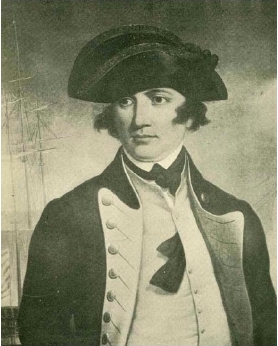

Worcester MA while suing his arch rival Samuel Ward for slander.Below: Stephen's brother, Esek Hopkins, by Martin Johnson Heade, Brown University Portrait Collection  Stephen

Hopkins is one of the subjects of an early American painting (1755) by

John Greenwood entitled "Sea Captains Carousing in Surinam",

the original of "Dogs Playing Poker" genre. Surinam (Suriname)

was a Dutch colony on the North coast of South America known for its

slave plantations. It was a predominant trading destination for Rhode

Island merchants during the 18th century who exchanged lumber, horses,

rum, and African slaves for sugar, coffee, and cocoa in what is known

as the Triangular Trade. While we have not discovered any direct

dealings Stephen Hopkins had in the slave trade, he certainly fits with

the profiles of those that did. Charles Rappleye in Sons of Providence (p57) indicates

that Stephen Hopkins did indeed own slaves, something not unusual for

upperclass families in Providence at the time. Esek Hopkins was a

mariner who often sailed for the Brown family, and commanded the

disasterous slave trading voyage of the Sally in 1764, during which most of

his cargo of 140 African slaves died. Details of the

voyage of the Sally, as well

as original source documents, and more information about Rhode Island's

involvement in slavery are found at Brown University's

Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice. Esek Hopkins later

went on to become the first commanding officer of the infant US Navy (see more at

JohnBHopkins.htm) Stephen

Hopkins is one of the subjects of an early American painting (1755) by

John Greenwood entitled "Sea Captains Carousing in Surinam",

the original of "Dogs Playing Poker" genre. Surinam (Suriname)

was a Dutch colony on the North coast of South America known for its

slave plantations. It was a predominant trading destination for Rhode

Island merchants during the 18th century who exchanged lumber, horses,

rum, and African slaves for sugar, coffee, and cocoa in what is known

as the Triangular Trade. While we have not discovered any direct

dealings Stephen Hopkins had in the slave trade, he certainly fits with

the profiles of those that did. Charles Rappleye in Sons of Providence (p57) indicates

that Stephen Hopkins did indeed own slaves, something not unusual for

upperclass families in Providence at the time. Esek Hopkins was a

mariner who often sailed for the Brown family, and commanded the

disasterous slave trading voyage of the Sally in 1764, during which most of

his cargo of 140 African slaves died. Details of the

voyage of the Sally, as well

as original source documents, and more information about Rhode Island's

involvement in slavery are found at Brown University's

Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice. Esek Hopkins later

went on to become the first commanding officer of the infant US Navy (see more at

JohnBHopkins.htm)In 1751, Stephen Hopkins was chosen Chief Justice of the Superior Court, in which office he continued until 1754 (there was no such thing as a Supreme Court at the time). He helped set up a public subscription library in Providence in the 1750s and he himself cataloged its first collection. He helped found the influential newspaper Providence Gazette and Country Journal in 1762. At the Albany Congress (1754), he cultivated a friendship with Benjamin Franklin and assisted him in lobbying a plan of colonial union, and arranging for an alliance with the Indians, in view of the impending war with France. Hopkins wrote A True Representation of the Plan Formed at Albany (1755) in hope of converting the opposition in Rhode Island. While the plan was approved by the Albany Congress, the individual colonies eventually rejected the idea. During the ensuing French & Indian war, Governor Hopkins was very active in promoting the enlistment of volunteers for the service; Hopkins raised a volunteer corps, and was placed at its head; but its services were not needed, and it was disbanded. He acted as first chancellor of Rhode Island College (later Brown University), founded in 1764 at Warren, and 6 years later he and the Brown brothers were instrumental in relocating it to Providence, and served as chancellor until 1785. He also held membership in the Philosophical Society of Newport. About this time, Hopkins took over leadership of the colony's radical faction, supported by Providence merchants. For more than a decade, it bitterly fought for political supremacy in Rhode Island with a conservative group in Newport, led by Samuel Ward, a political enemy of Hopkins. In 1756, Hopkins was elected Governor of the colony and he held that office during nine terms (at the time a term as Governor lasted only a year) on and off (1755-1756, 1758-1761, 1763-1764, and 1767), as he and Samuel Ward played musical chairs with the Governorship. These annual battles for the Governor's office took on a farcical air, with Hopkins supporters John and Moses Brown buying up votes; the Ward camp did likewise. His sea trading companion Joseph Wanton helped the Hopkins faction in the Newport area. He served as Deputy Governor during Hopkins' last two terms, later becoming Governor himself. Overall, the Hopkins faction helped wrestle supremacy within the Colony by Providence (Plantations) over Newport (Rhode Island). While he was Governor, Hopkins had a disagreement with William Pitt, Prime Minister of England, regarding illegal molasses trade with the French colonies. Hopkins was one of the earliest and most vigorous champions of colonial rights, and in 1764 took aim, writing under the pseudonym "P", in the Providence Gazette with an essay entitled "Essay on the Trade of the Northern Colonies." Per Carroll's Rhode Island: Three Cernturies of Democracy, p234: The General Assembly, in

July

[1764], appointed

Governor Hopkins, Daniel

Jencks

and Nicholas Brown a "committee of correspondence" to "confer and

consult

with any committee or committees that are or shall be appointed by any

of the British colonies upon the continent of North America, and to

agree

with them upon such measures as shall appear to them necessary and

proper

to procure a repeal of the . . . sugar act . . . and also the act

. . . for levying several duties in the colony, or in procuring the

duties

in the last mentioned act to be lessened; also to prevent the levying a

stamp duty upon the North American colonies and, generally, for the

prevention

of all such taxes, duties or impositions that may be proposed to be

assessed

upon the colonists which may be inconsistent with their rights and

privileges

as British subjects." In October, Governor Hopkins, Nicholas

Tillinghast,

Joseph Lippitt, Joshua Babcock, Daniel Jencks, John Cole and Nicholas

Brown

were appointed a committee "to prepare an address to his majesty for a

redress of our grievances in respect to the duties, impositions, etc.,

already laid and proposed to be laid on this colony."

Iin 1770 Hopkins was appointed to a Providence Committee ofIinspection, basically a group that attempted to enforce the agreements of nonimportation of British goods among area merchants. When the British revenue schooner HMS Gaspee was attacked and burned by compatriots of Hopkins in 1772, he gave immediate sage advice to help limit Royal reprisals over the raid, and later so much as declared that Rhode Island courts would not cooperate with the Gaspee investigatory commission, by refusing to hand over any citizen so indicted to the British Admiralty stating, "Then, for the purpose of transportation for trial, I will neither apprehend any person by my own order, nor suffer any executive officer in the Colony to do it." (Bartlett, RI Colonial Record, VII:60.). He and Deputy Governor Darius Sessions were also able to convince the Commission of Inquiry to limit their powers so as to not usurp the local courts within the Colony. As Chief Justice of the Superior Court, Stephen Hopkins demonstrated a particular reluctance to find suspects indictable for trial, which would have greatly aided the British cause. In March of 1773 the Virginia House of Burgess,

largely in response to the threats to American liberties posed by the

Gaspee Affair, created the first permanent intercolonial committee of

correspondence. These resolutions were sent to Rhode Island by

Peyton

Randolph,

Speaker of the Virginia House of Burgesses, and laid before the General

Assembly at the May session. The Assembly adopted resolutions

creating a standing committee of correspondence for Rhode Island,

including Stephen

Hopkins,

Metcalfe Bowler, Moses Brown, John Cole, William Bradford, Henry

Marchant

and Henry Ward. In 1773 in keeping with the directives of Quaker leadership of the time, Hopkins freed his slaves that he had acquired through marriage. In 1774, again elected to the General Assembly, he authored a bill enacted by the Rhode Island legislature that prohibited the importation of slaves into the colony—one of the earliest antislavery laws in the United States. <>He carried on with his duties in the legislature and Superior Court while a Member of the Continental Congress (1774-76). He was elected along with Samuel Ward (later replaced by William Ellery) to the Continental Congress in Philadelphia in August 1774. "to represent the people of this colony in a general congress of representatives from the other colonies, at such time and place as shall be agreed upon by the major part of the committees appointed or to be appointed by the colonies in general." These were the first delegates from any colony elected to the Congress of 1774.Paul Revere relates one interesting snippet upon meeting Stephen Hopkins for the first time, contained in The Life and Recollections of John Howland, p198:. One evening [in 1774], a

number

of the gentlemen seated around the fire, were conversing on the

engrossing subject of the day. They generally expressed the opinion

that the next arrival from England would bring news of the repeal of

the obnoxious [Intolerable ]acts then complained of. Governor

Hopkins, who was walking the floor, and had not joined in the

conversation, stopped, and facing the company said, ' Gentlemen, those

of you who indulge this opinion, I think deceive yourselves. Powder and

ball will decide this question. The gun and bayonet alone will finish

the contest in which we are engaged, and any of you who cannot bring

your minds to this mode of adjusting the question, had better retire in

time, as it will not, perhaps, be in your power, after the first blood

shall have been shed.'

"Knowing nothing of armed

ships,

he (Adams) made himself expert,

and would call his work on the naval committee the pleasantest part of

his labors, in part because it brought him in contact with one of the

singular figures in Congress, Stephen Hopkins of Rhode Island, who was

nearly as old as Franklin and always wore his broad-brimmed Quaker hat

in chamber. Adams found most Quakers to be 'dull as beetles,' but

Hopkins was an exception. A lively, learned man ... he suffered the

loss of three sons at sea, and served in one public office or other

continuously from the time he was twenty-five. The old gentlemen loved

to drink rum and expound on his favorite writers. The experience and

judgment he brought to the business of Congress were of great use, as

Adams wrote, but it was in the after-hours that he 'kept us alive.'

His custom was to drink nothing all day, nor 'til eight o'clock in the

evening, and his beverage was Jamaica spirits and water ... Hopkins

never drank to excess, according to Adams, but all he drank was

promptly converted into wit, sense, knowledge, and good humor."

While at Congress, Hopkins served on the

committees that prepared the

Articles of Confederation. Hopkins' knowledge of the shipping

business made him particularly useful as a

member of the Naval Committee. He persuaded the Congress in 1775 to

outfit 13

armed vessels and to commission them as the Navy of the united

colonies. He also saw to it that Rhode Island received a contract to

out

fit two of these, and

appointed his brother Esek Hopkins as its commander-in-chief. His

wife's cousin, Abraham Whipple, was

commissioned to the rank of Commodore, while Stephen Hopkins' nephew, John B. Hopkins, was commissioned as

Lieutenant. One vignette retold in the Providence Journal (March 8, 2007,

pB5) depicts the rather humble Quaker values of the Hopkins household: General

Washington’s first visit was on April 5, 1776. He was on his way to

take command of the Continental Army in Boston. Hopkins himself was in

Philadelphia, at the Continental Congress. His daughter-in-law served

as host. Her family wanted to lend her better china for the occasion.

“What’s good enough for my father,” she is said to have replied, “is

good enough for General Washington.”

Continued ill health compelled Hopkins to retire in September 1776, a month after he signed the Declaration. He declined subsequent reelections to Congress, but sat in the State legislature from 1777 through 1779, and took part in several New England political conventions. He withdrew from public service about 1780. His second wife Ann died in 1782, and Stephen Hopkins himself died on July 13, 1785 in Providence at the age of 78. It is said he retained full possession of his faculties to the end, and he was interred in the Old North Burial Ground of Providence, where both of his wives had preceded him. "A vast assemblage of persons, consisting of judges of the courts, the president, professors and students of the college, together with the citizens of the town, and inhabitants of the state, followed the remains of this eminent man to his resting place in the grave". Details of his funeral procession and eulogy are contained in the 21 and 23July1785 editions of the Providence newspapers. A sad historical footnote is added by John Howland in Stone, Edward Martin. The Life and Recollections of John Howland, Late President of the Rhode Island Historical Society. Providence, Geo. H. Whitney, 1857, p47: He left a large trunk of

papers

connected with the transactions of his public life. After his

decease, an unsuccessful attempt was made by Moses Brown to obtain them

for safe keeping, and in the great storm of September, 1815, the tide

swept through the house where they were lodged, and they were carried

off and lost in the multitude of waters.

The town of Hopkinton, Rhode Island was later named

after him. The SS Stephen Hopkins,

a liberty ship named in his honor, was the first US ship to sink a

German surface warship in World War II. In the musical 1776,

which tells the story of the drafting and signing of the Declaration of

Independence, Stephen Hopkins is a main character. He is depicted as a

well meaning but cantankerous drunkard whose force of personality helps

keep the Continental Congress together. Most historians consider that

depiction to be a bad rap: our Stephen Hopkins had converted to

Quakerism, and most likely did not drink at all. Our Stephen

Hopkins is also not to

be confused with others of that name, including one that was an early

settler of the Plymouth Plantation, nor the current day movie director. |

| In recognition of the 300th anniversary of the birth of Stephen Hopkins, The TriCentennial Commission has established a website complimenting much of the information presented above at http://StephenHopkins.org. |

| For dereliction of his duty to his King, and by obstructing the Gaspee Commission of Inquiry while Chief Justice of Rhode Island, we recognize Stephen Hopkins as an unindicted co-conspiritor in the Gaspee Affair. |

| From

Quahog.org:

Stephen Hopkins' gravestone inscriptions at the Old North Burial

Ground, Providence, RI:

West side SACRED

TO THE MEMORY OF

THE

ILLUSTRIOUS

STEPHEN HOPKINS, OF REVOLUTIONARY FAME, ATTESTED BY HIS SIGNATURE TO THE DECLARATION OF OUR NATIONAL INDEPENDENCE. GREAT IN COUNCIL, FROM SAGACITY OF MIND; MAGNANIMOUS IN SENTIMENT, FIRM IN PURPOSE, AND GOOD, AS GREAT, FROM BENEVOLENCE OF HEART; HE STOOD IN THE FRONT RANK OF STATESMEN AND PATRIOTS. SELF-EDUCATED, YET AMONG THE MOST LEARNED OF MEN; HIS VAST TREASURY OF USEFUL KNOWLEDGE, HIS GREAT RETENTIVE AND REFLECTIVE POWERS, COMBINED WITH HIS SOCIAL NATURE, MADE HIM THE MOST INTERESTING OF COMPANIONS IN PRIVATE LIFE. South side HIS

NAME IS ENGRAVED

ON THE IMMORTAL RECORDS OF THE REVOLUTION, AND CAN NEVER DIE: HIS TITLES TO THAT DISTINCTION ARE ENGRAVED ON THIS MONUMENT, REARED BY THE GRATEFUL ADMIRATION OF HIS NATIVE STATE, IN HONOR OF HER FAVORITE SON. East side HOPKINS

BORN MARCH 7, 1707 DIED JULY 13, 1785 North side HERE

lies the man in fateful hour,

Who boldly stemm'd tyrannic pow'r. And held his hand in that decree, Which bade America BE FREE! —Arnold's poems |

Sources

consulted:

Bibliography from the Congressional Biography of Stephen Hopkins:

|

| Genealogical

Addendum: Stephen HOPKINS Birth: 7 MAR 1707 in Cranston, RI Death: 13 JUL 1785 in Providence, RI Father: William HOPKINS (1682) son of William Hopkins (1647) and Abigail WHIPPLE Mother: Ruth WILKINSON b: 31 JAN 1686, dau of Samuel WILKINSON & Plain WICKENDEN Marriage1 1726: Sarah SCOTT (c1707 - 1753) dau of Silverman SCOTT c1665 & Jeanna JENCKS Children: (all born in Scituate, Providence, RI) Marriage2 1755: Ann SMITH b:5OCT1717 in Providence, dau of Benjamin SMITH & Mercy ANGELL. Died 26 JAN 1782 Stephen Hopkins' brother John married a Catherine Turpin., and his sister Hope married a Henry Harris. According to Whipple.org, Gaspee raid leader Abraham Whipple was the brother-in-law to Stephen Hopkins. Actually, Abraham Whipple's wife was Sarah Hopkins, the daughter of John Hopkins, (the brother of Stephen), so Abe's wife was Steve's cousin. |

| Back to Top | Back to Gaspee Virtual Archives |

Right: Portrait

detail as depicted in "Declaration of

Independence" by

John Trumbull (1819),

Right: Portrait

detail as depicted in "Declaration of

Independence" by

John Trumbull (1819),

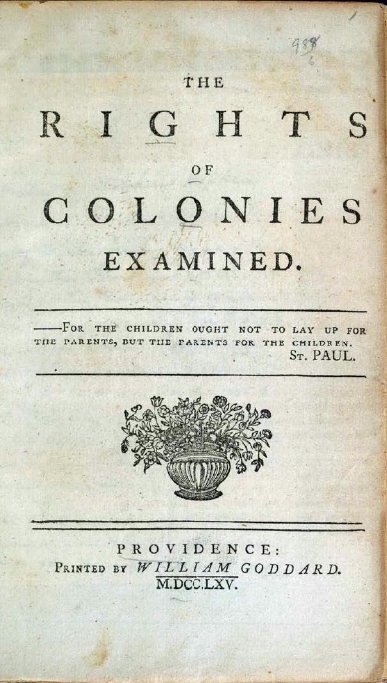

Left:

Hopkins' famous pamplet

Left:

Hopkins' famous pamplet