Gaspee Virtual Archives Virtual Archives |

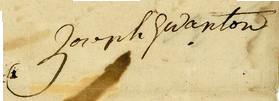

| Governor Joseph Wanton

(1705-1780) The Gaspee Days Committee at www.gaspee.COM is a civic-minded nonprofit organization that operates many community events in and around Pawtuxet Village, including the famous Gaspee Days Parade each June. These events are all designed to commemorate the 1772 burning of the hated British revenue schooner, HMS Gaspee, by Rhode Island patriots as America's 'First Blow for Freedom' TM. Our historical research center, the Gaspee Virtual Archives at www.gaspee.ORG , has presented these research notes as an attempt to gather further information on one who has been suspected of being associated with the the burning of the Gaspee. Please e-mail your comments or further questions to webmaster@gaspee.org. |

Left: Governor

Joseph Wanton. Artist unknown,. Used with permission, Redwood

Library, Newport Left: Governor

Joseph Wanton. Artist unknown,. Used with permission, Redwood

Library, Newport

Governor Joseph Wanton was born

in

Newport,

RI on August 15, 1705 and was the son of a wealthy merchant William

Wanton

who served as Rhode Island Governor under the Royal Charter in

1732-1733.

William was the son of Edward Wanton, who emigrated from London to

Boston

about the year 1658. William's brother, John Wanton, was likewise a

successful

Newport merchant and succeeded him as Governor from 1734 through

1740.

Williams cousin, Gideon, yet another Newport merchant, was Governor of

the colony in 1745 and 1747. William Wanton was raised a Quaker and his mother, Ruth

Bryant, a

Presbyterian. To make peace, they both converted into Anglican

church, and raised their children in the Church of England. According

to Elmer E. CornellAA, this

fact may have

influenced Wanton to be perceived as more loyalist than many of his

fellow Rhode Islanders who were predominantly Baptists and

Congregationalists. The

Joseph Wanton of our concern was born on August 15, 1705, the

son

of Governor William Wanton. He graduated from Harvard in 1751 and

then, following his family interests, he also became a successful

merchant

of the area. We note that he was part owner of the privateer

ships, Charming Betty,

and Scorpion, during

the French and

Indian war, and Joseph Wanton was the master aboard the King of Prussia, a privateer during

the this time that was captured by the French in 1758 with

a cargo gold dust, rum, and 54 slavesAB.

Many such privateers out of Newport were actually running in the slave

trade. His image was captured in 1755 by John Greenwood in his famous

painting "Sea Captains Carousing in Surinam"--the oringinal of "Dogs

Playing Poker" genre. Surinam

(Suriname) was a Dutch colony on the North coast of South America known

for its slave plantations. It was a predominant trading destination for

Rhode Island merchants during the 18th century who exchanged lumber,

horses, rum, and African slaves for sugar, coffee, and cocoa in what is

known as the Triangular Trade.

His family connections assisted in his rapid rise in

the public service ranks, and he was elected Lieutenant-Governor of

Rhode

Island in 1764 and 1767 under his friend, Governor Stephen

Hopkins. In May of 1769, Joseph Wanton was chosen

as successor of Governor Josias Lyndon. Wanton was not above nepotism,

and quickly appointed his son, William, to the patronage job of 'naval

officer', in charge of provincial customs record keepingA1. During his term in office, Wanton

encountered

the whole Gaspee Affair beginning in May of 1772. Dep. Gov. Darius

Sessions petitioned the Governor to intercede on the behalf of the

merchants and sea traders who were being continuously harrassed by Lt.

Dudingston and the Gaspee.

Wanton wrote to Dudingston demanding to see his commission, but

Dudingston refused and referred the matter to his superior, Admiral

Montagu. This led to a series of insulting and threatening

letters between Wanton and Montagu over their respective authorities

within the Colony of Rhode Island. Montagu at one point

threatened to "hang as pirates" any citizens of Newport attempting to

interfere with the Gaspee's

mission. Once the Gaspee

had been attacked and burned in June of 1772, Wanton took certain

measures to protect the Colony of Rhode Island from the impending wrath

of the British government. By promptly offering a reward for

information regarding the Gaspee attackers, he demonstrated that the

Colony treated the matter seriously, at least on paper. The British had automatically assumed the incident

occurred in Newport harbor. Offended

by this unwarranted presumption, Governor Wanton penned a hasty letter

to Lord Dartmouth in which he assured the angry minister that the event

took place "at least 30 miles off and none of the Newport people could

have had any hand in it." What he did not say was that the

Newport mob stood ready to support its Providence counterparts had it

been necessary.1

Governor Wanton was appointed chairman of the special commission of inquiry set up by the British government to discover and bring to justice those persons who attacked and burned the British revenue schooner, HMS Gaspee, in 1772. It is clear, in retrospect, that Wanton desired to mitigate any damages to Rhode Island arising from the affair. While his goal was not likely one of seeking independence from the mother nation, he most probably desired to protect the Rhode Island Charter from being rescinded by London. By demanding that he be appointed chairman of the Commission, Wanton positioned himself to be able to limit the effectiveness of the inquiry by putting his spin on any evidence presented. While no proof of collusion can be had, it is quite likely that Wanton conspired with his Deputy Governor Darius Sessions to provide creative counter-testimony to the actual facts of the case. Judge Staples notes in his Documentary History of the Destruction of the Gaspee (1990 ed, p30): There is little room to doubt but that Gov. Wanton and the officers of the colony would have been satisfied that the authors of the mischief should remain undiscovered; although their duty as officers, and their interests required them to exhibit a great zeal and loyalty on the occasion.4Deasy writes in a similar note in his Introduction to the 1990 republication of Documentary History of the Destruction of the Gaspee (p. xxxix): Although it is unlikely that his business connections with the Browns compromised his judicial integrity, nonetheless Wanton simply did not quite fit into the same category as the other four [commission judges]. True, when the Revolution came, he sided with the Crown, but even this choice has been recently somewhat qualified.[Elmer E. Comwell, "The Ordeal of Governor Joseph Wanton," Rhode Islander (Providence Sunday Journal magazine), June 9, 1974, pp. 32-39] It might not, however, "be doing great injustice to the memories and the character" of the commissioners to suggest, as Stiles did, that the inquiry was hardly to their liking and they "were inclined to interpret it in the mildest sense."[Stiles, Diary, I. 349]4Governor Wanton was able to create yet more disruption for the Gaspee commission by revealing to the General Assembly the contents of a letter written to him by Lord Dartmouth discussing the British intent to have the perpertrators of the Gaspee attack tried in London and publicly executed for 'high treason'. Deasy explains, "Dartmouth was indignant over the public disclosure of this letter, which presumably revealed the real basis of Crown policy. It is not clear that the charge of treason dramatically changed the nature of colonial resistance to the inquiry, but it certainly put it into a very different context." Documentary History of the Destruction of the Gaspee (1990 ed, p. xl).4 Joseph Wanton was annually re-elected Governor through May,

1775. By

this time, however, the mood of the General Assembly had changed to

favor

independence from the Mother Country, and in 1775 the Assembly passed a

resolution calling for an Army of Observation to be raised "to repel

any

insult or violence that may be offered to the inhabitants; and also, if

it be necessary, for the safety and preservation of any of the

colonies,

to march out of this colony, and join and cooperate with the force of

tlie

neighboring colonies." Wanton feared such a bold and insolent

move,

and he objected strongly to the passage of the resolution, which was

ultimately

passed over his objections. Catherine Williams in Biography of

Revolutionary

Heroes: Containing the Life of Brigadier Gen. William Barton and also

of

Captain Stephen Olney. Providence, Published by the author, 1839,

p154 states ..... he very politely,

but

firmly declined the honor of putting his name to a paper (which might

hang him,) which his conscience could not approve, and renewed his

protestations that he had been perfectly willing to go with his

suffering brethren in remonstrance, appeal and petition, to redress

their grievances, while that alone was resorted to, but he was not

prepared for an appeal to arms, and should not, by his name, sanction

any such unlawful and rebellions proceedings.5

Nicholas Cooke (who is pictured drunk at the Surinam bar with his friend Wanton c1755) was appointed as Wanton's successor to become Governor, and served until 1778. Mr. Cooke had become convinced that the warlike measures of the Assembly were correct, and entered heartily into all their views. The 'Army of Observation' was ultimately raised and consisted of over 1,500 Rhode Island men, later led by Nathanael Greene.

Wanton continued to live in Newport, albeit, in relative obscurity. He at one time fled to the safety of the Capt. Wallace's flagship, HMS Rose from where he refused to recognize the legitamacy of the coup that deposed him as Governor. While the British occupied Newport in December 1776 through October 1779 not much else was heard from him, although he apparently did have success in marrying off some of his daughters to various Britishers. Mohr states that, Whatever may have been the real feeling which he favored for the English government, he committed no act which was followed by the confiscation of his estate. When the British evacuated the town, and the Americans returned to its possession, he remained without being molested during the brief period which elapsed before his death...3According to Don D'AmatoA2, the victorious Americans did, however, take away his estate. But there is also considerable confusion between (and intermixing) of the histories of Governor Joseph Wanton and his son, Joseph Wanton, Jr. by many historians, and Joseph Wanton, Jrs' house in Newport was indeed confiscated. Governor Joseph Wanton died in Newport in 1780 and is buried in the Clifton Buring Ground. Governor Wanton's wife was Mary, daughter of John Still Winthrop, of New London. CT, by whom he had three sons and five daughters. Mary was the great-granddaughter of Connecticut Colonial Governor, John Winthrop, Jr. 1) Joseph, who was for a time a Deputy Governor of Rhode Island and an ardent loyalist whose property was confiscated after the Revolution. |

| Sources: AACornell, Jr, Elmer E.: "The Ordeal of Governor Joseph Wanton", Rhode Islander, The Providence Sunday Journal Magazine, June 9, 1974, pp34-39 ABSheffield Wiiliam P.: An Address, (Newport: JP Sanborn, 1883), p56. A1Gerlach,

Larry R. "Charles Dudley and the Customs Quandary of Pre-Revolutionary

Rhode Island." Rhode Island

History, Spring 1971, pp52-59. A2D'Amato, Donald. "A Glimpse of Rhode Island's Past: A governor is deposed in 1775" Warwick Beacon, June 17, 2009. 1Crane,

Elaine

Forman. A Dependent People: Newport,

Rhode Island in the Revolutionary Era, Fordham University

Press, New York, 1992. p116. 2Lossing, Benson J. Pictoral Field Guide to the Revolution, Vol. I. Harper Brothers, New York, 1859, Chapter XXVII.. 3Mohr, Ralph S. Governors for Three Hundred Years, 1638-1959, Rhode Island and Providence Plantations. Revised Edition. Oxford Press, 1959. p184-185 4Staples, William R. Documentary

History

of the Destruction of the Gaspee, Introduction by Richard

Deasy.

Rhode Island Publications Society, 1990. See Also: Wikipedia: Joseph Wanton |

Left:

Left: